Some people point to the enormous sums spent by the fossil fuel industry to confuse the public about the causes and consequences of climate change and about the future availability of fossil fuels. This is certainly a very big factor. Polls show that the American public's acceptance of the scientific consensus on climate change has declined in recent years coincident with a very strong propaganda push by the industry (though that acceptance has rebounded recently as record summer heat has changed some minds back). When it comes to energy supplies, industry television ads currently fill the airways in America with claims of 100 years of natural gas. This is despite that fact that the latest government estimates of future U.S. natural gas supplies have been dramatically slashed.

But I want to get at why people are susceptible to such manipulation in the first place. After all, the truth about climate change is now available practically worldwide to anyone who has a computer or even access to a library. And, the figures on oil production, which has been flat since 2005, are available from official government websites.

The answer starts with the issue of complexity. Issues such as climate change and resource depletion are really a complex set of interconnected issues that include population, per capita consumption, geology, climate science, infrastructure, technology, ideology, politics, economics, and, well, you get the idea. Even very intelligent, committed people have a hard time keeping up with and understanding the information available. In addition, climate change and resource depletion tend to be abstract and not subject to verification by the average individual. Simple observation on any given day cannot tell you whether the climate is changing or whether critical resources are being depleted.

All this makes it easy to send misleading and false messages to the public about these issues since the recipients have little information from direct observation to go on. Instead, because much of the public cannot grasp these issues or sense them as problems in their everyday lives, they are susceptible to appeals that activists aren't really concerned about those issues; rather, their agenda is to control somehow the lives of others through government regulation and taxation. It's never explained exactly why activists would want to do this for its own sake since the taxes and regulation would hit them as well. But this twin threat is a potent one in the American psyche in particular. (Oddly, those who push intrusive surveillance of the public, the destruction of civil liberties and privacy in the name of protecting us from terrorism, and the borrowing of trillions of dollars to finance wars based on false premises don't seem to warrant the same concern. Nor do large corporations which control so much of our lives.)

There is, of course, the natural human prejudice that the future will pretty much look like the recent past though history tells us that change, sometimes rapid, catastrophic change, can occur when it is least expected. (Of course, you would have to read history to know this.) And, that's why appeals to technological solutions work particularly well. For some reason, people generally readily dismiss the ill and unintended effects of technology and believe that all future technology will be free of side effects. One reason could be the almost miraculous power that technology has made available to the individual in the areas of communication, transport, and even weapons. Power, of course, doesn't mean no side effects, but it tends to obscure the downside of our technology.

The feeling among the populace is generally that there is no problem that technology cannot solve. Now, think about what it would take to explain why relying on technological advances alone is a risky course. You would be forced to deal with complexity after complexity.

So, if it's not the availability of information and communication that brings about consensus, what does? Let me suggest that it is the confluence of values that makes consensus possible. Where values converge even if methods don't, there is a chance to find consensus. The idea that one could increase control over one's life through localized energy sources, for instance, might be a good place to start. Bringing control closer to home has been one of the major driving forces behind the local food movement. It is, of course, not less complex for the individual to reassert control over his or her life. New skills such a growing food and new ways of cooperating such as community gardens and community-based power require more involvement, not less.

Letting a corporation handle all the complexity for us at the grocery store and the electric generating plant doesn't reduce overall complexity in society; it merely shifts it to someone else and makes us more subject to the other person's or organization's agenda and weaknesses.

We shouldn't abandon the search for effective communication strategies. We need to find better ones. But we should couple our search with a search for common values that can pave the way to consensus. With that focus our vast instantaneous worldwide communications system could then become a far better ally in addressing the major issues of our time.

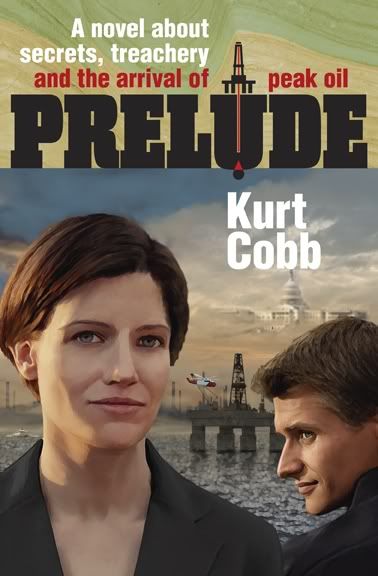

Kurt Cobb is the author of the peak-oil-themed thriller, Prelude, and a columnist for the Paris-based science news site Scitizen. His work has also been featured on Energy Bulletin, The Oil Drum, 321energy, Common Dreams, Le Monde Diplomatique, EV World, and many other sites. He maintains a blog called Resource Insights.

Kurt Cobb is the author of the peak-oil-themed thriller, Prelude, and a columnist for the Paris-based science news site Scitizen. His work has also been featured on Energy Bulletin, The Oil Drum, 321energy, Common Dreams, Le Monde Diplomatique, EV World, and many other sites. He maintains a blog called Resource Insights.